Manipulating Strings¶

Introduction

String formatting

String method

Text is one of the most common forms of data our programs will handle. We already know how to concatenate two string together with the + operator, but we can do much more than that!

We can extract partial strings from string just like sequence, add or remove spacing, convert letters to lowercase or uppercase, and check that strings are formatted correctly!

String¶

There are several ways to create a new string; the simplest is to enclose the elements in single, double or triple quotes:

type(''), type(""), type("""""")

(str, str, str)

print("I'am fine")

I'am fine

A string is a sequence that maps index to case sensitive characters and thus belongs to sequence data type. Anything that we can apply to the sequence can also be applied to string. For instance, we can access the elements (characters) one at a time with the bracket operator.

fruit = 'banana'

fruit[1]

'a'

So "b" is the 0th letter ("zero-th") of "banana", "a" is the 1th letter ("one-th"), and "n" is the 2th ("two-th") letter.

len() can be used to return the number of characters in a string:

len(fruit)

6

We can use negative indices, which count backward from the end of the string.

fruit[-1], fruit[-2]

('a', 'n')

Slicing also works on string to extract a substring from the original string. Remember that we can slice sequences using [start:stop:step]. The operator [start:stop] returns the part of the string from the "start-th" character to the "stop-th" character, including the first but excluding the last with step=1.

s = 'Cool-Python'

print(s[:5]) #same as s[0:5]

print(s[5:]) #same as s[5:len(s)]

print(s[::2]) #same as s[0:len(s):2]

print(s[::]) #same as s[:] and s[0:len(s):1] => copy the string

print(s[::-1]) #same as s[-1:-(len(s)+1):-1] => reverse the string

Cool- Python Co-yhn Cool-Python nohtyP-looC

s = "hello" # `Strings` are "immutable", which means that it cannot be modified

s[0] = 'y'

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) ~\AppData\Local\Temp\ipykernel_6820\2526582181.py in <module> 1 s = "hello" # `Strings` are "immutable", which means that it cannot be modified ----> 2 s[0] = 'y' TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

The "object" in this case, is the string and the "item" is the character we tried to assign. The best we can do is create a new string that is a variation on the original:

print(id(s))

s = 'y' + s[1:len(s)]

print(id(s))

print(s)

2544442647920 2544446710832 yello

A lot of computations involve processing a string one character at a time. Often they start at the beginning, select each character in turn, do something to it, and continue until the end. The traversal of string is just like we see before:

# Test if s contains 'o'

b = False

for char in s: # Retrieve item (character) one by one

if char == 'o':

b = True

break

print(b)

True

The in and not in operators can be used with strings just like with list. An expression with two strings joined using in or not in will evaluate to a Boolean True or False:

print('o' in 'Hello')

print('cats' not in 'cats and dogs')

True False

display_quiz(path+"string1.json", max_width=800)

Escape Characters¶

An escape character lets us use characters that are otherwise impossible to put into a string. An escape character consists of a backslash (\) followed by the character we want to add to the string.

For example, the escape character for a single quote is \'. We can use this inside a string that begins and ends with single quotes.

spam = 'Say hi to Bob\'s mother.'

spam

"Say hi to Bob's mother."

Python knows that since the single quote in Bob\'s has a backslash, it is not a single quote meant to end the string. The escape characters \' and \" let us put single quotes and double quotes inside our strings, respectively.

| Escape character | Prints as |

|---|---|

\' |

Single quote |

\" |

Double quote |

\\ |

Backslash |

\t |

Tab |

\n |

Newline (line break) |

print("Hello there!\nHow are you?\n\tI\'m doing fine.")

Hello there! How are you? I'm doing fine.

display_quiz(path+"escape.json", max_width=800)

> Exercise 1: Ask LLM about the concept of escape character and list some examples¶

Refer to https://hackmd.io/@phonchi/LLM_Tutor

Raw Strings¶

We can place an r before the beginning quotation mark of a string to make it a raw string. A raw string completely ignores all escape characters and prints any backslash that appears in the string.

print(r'That is Carol\'s cat.')

That is Carol\'s cat.

Because this is a raw string, Python considers the backslash as part of the string and not as the start of an escape character.

Raw strings are helpful if we are typing strings that contain many backslashes, such as the strings used for Windows file paths like r'C:\Users\Al\Desktop'.

Putting Strings Inside Other Strings¶

Putting strings inside other strings is a common operation in programming. So far, we've been using the + operator and string concatenation to do this:

name = 'AI'

age = 33

language = 'Python'

print("Hey! I'm " + name + ", " + str(age)+ " old and I love " + language + " Programing")

Hey! I'm AI, 33 old and I love Python Programing

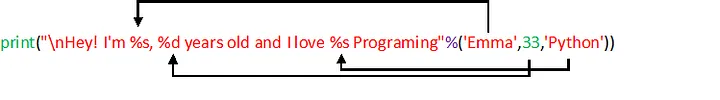

However, this requires a lot of tedious typing. A simpler approach is to use string interpolation. The format operator, % allows us to construct strings, replacing parts of the strings with the data stored in variables.

The first operand is the format string, which contains one or more format specifiers that specify how the second operand is formatted. The result is again a string.

For example, the format specifiers %d means that the second operand should be formatted as an integer ("d" stands for "decimal"):

print("\nHey! I'm %s, %d years old and I love %s Programing"%(name,age,language)) # Like the printf in C

Hey! I'm AI, 33 years old and I love Python Programing

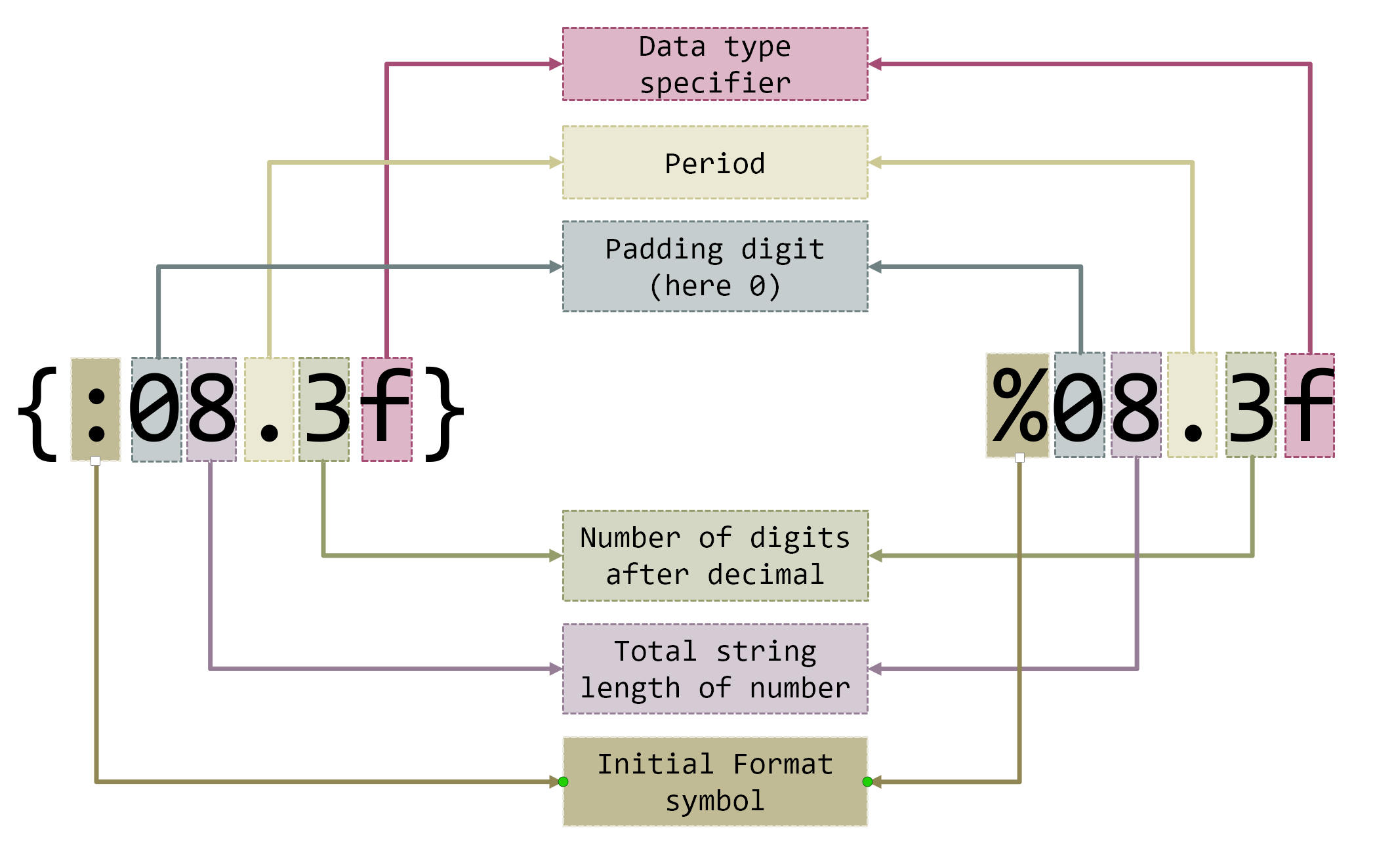

We can have more control over the formatting, for instance:

a = 32

b = 32.145

print('a=%4d, b=%6.2f' % (a,b))

a= 32, b= 32.15

a = 32

b = 32.145

print(f'a={a:4d}, b={b:6.2f}')

a= 32, b= 32.15

Python 3.6 introduced f-strings (The f is for format), which is similar to string interpolation except that braces are used instead of %, with the variables or expressions placed directly inside the braces.

Like raw strings, f-strings have an f prefix before the starting quotation mark.

print(f"\nHey! I'm {name}, {age+2} years old and I love {language} Programing")

Hey! I'm AI, 35 years old and I love Python Programing

We can have more control with the f-string besides the field width, like specifying left, right and center alignment with <, > and ^. Note now the format specifiers are placed after the variable separated by a colon:

print(f'[{a:<15d}]') # a = 32, b = 32.145

print(f'[{b:^9.2f}]')

[32 ] [ 32.15 ]

In addition, we can use + before the field width specifies that a positive number should be preceded by a +. A negative number always starts with a -. To fill the remaining characters of the field with 0s rather than spaces, place a 0 before the field width (and after the + if there is one):

print(f'[{a:+10d}]')

print(f'[{a:+010d}]')

[ +32] [+000000032]

display_quiz(path+"string2.json", max_width=800)

Exercise 2: Assuming we are designing a word game called "The Mysterious Island" and we need to print the statistics of the player each time the game begins. Try to complete the following function that receives the variables from the game and displays the information that right aligns with each other using the f-string:¶

Player1 Stats:

Health: 100/100

Gold: 0/150

Experience: 50.00/60.00

Player2 Stats:

Health: 60/100

Gold: 120/150

Experience: 40.00/60.00

Hint: The maximal width required for each row is 25.

def print_stats(player_name, health, experience, gold):

print(f"{player_name} Stats:")

print(f"Health:{____:____}/100")

print(f"Gold:{____:____}/150")

print(f"Experience:{____:____}/60.00")

game_title = "The Mysterious Island"

welcome_message = f'Welcome to "{game_title}" adventure!\n\n'

# 1. Print the welcome_message

print(welcome_message)

# 2. Use string and number formatting to print out the statistics

player_name = "Player1"

health = 100

gold = 0

experience = 50.000

print_stats(player_name, health, experience, gold)

print("\n")

player_name = "Player2"

health = 60

gold = 120

experience = 40.0

print_stats(player_name, health, experience, gold)

String method¶

Strings are an example of Python objects. An object contains both data (the actual string itself) and methods, which are effective functions that are built into the object and are available to any instance of the object.

Python has a function called dir(), which lists the methods available for an object.

print(dir(s))

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getnewargs__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'capitalize', 'casefold', 'center', 'count', 'encode', 'endswith', 'expandtabs', 'find', 'format', 'format_map', 'index', 'isalnum', 'isalpha', 'isascii', 'isdecimal', 'isdigit', 'isidentifier', 'islower', 'isnumeric', 'isprintable', 'isspace', 'istitle', 'isupper', 'join', 'ljust', 'lower', 'lstrip', 'maketrans', 'partition', 'removeprefix', 'removesuffix', 'replace', 'rfind', 'rindex', 'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split', 'splitlines', 'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate', 'upper', 'zfill']

The upper(), lower() Methods¶

The upper() and lower() string methods return a new string where all the letters in the original string have been converted to uppercase or lowercase:

spam = 'Hello, world!'

spam = spam.upper()

print(spam)

spam = spam.lower()

print(spam)

HELLO, WORLD! hello, world!

Note that these methods do not change the string itself but return new string values. If we want to change the original string, we have to call upper() or lower() on the string and then assign the new string to the variable where the original was stored!

This is why we must use spam = spam.upper() to change the string in spam instead of simply spam.upper().

The upper() and lower() methods are helpful if we need to make a case-insensitive comparison. For example, the strings 'great' and 'GREat' are not equal to each other. But in the following small program, it does not matter whether the user types Great, GREAT, or grEAT, because the string is first converted to lowercase.

print('How are you?')

feeling = input()

if feeling.lower() == 'great':

print('I feel great too.')

else:

print('I hope the rest of your day is good.')

How are you? I hope the rest of your day is good.

display_quiz(path+"string3.json", max_width=800)

The isX() Methods¶

There are several other string methods that have names beginning with the word is. These methods return a Boolean value that describes the nature of the string. Here are some common isX() string methods:

isupper()/islower()ReturnsTrueif the string has at least one letter and all the letters are uppercase or lowercaseisalpha()ReturnsTrueif the string consists only of letters and isn't blankisalnum()ReturnsTrueif the string consists only of letters and numbers and is not blankisdecimal()ReturnsTrueif the string consists only of numeric characters and is not blankisspace()ReturnsTrueif the string consists only of spaces, tabs, and newlines and is not blankistitle()ReturnsTrueif the string consists only of words that begin with an uppercase letter followed by only lowercase letters and is not blank

print('Hello, world!'.islower())

print('hello, world!'.islower())

print('hello'.isalpha())

print('hello123'.isalnum())

print('hello123'.isdecimal())

print(' '.isspace())

print('This Is Title Case'.istitle())

False True True True False True True

The isX() string methods are helpful when you need to validate user input. For example, the following program repeatedly asks users for their age and a password until they provide valid input:

while True:

print('Enter your age:')

age = input()

if age.isdecimal():

break

print('Please enter a number for your age.')

while True:

print('Select a new password (letters and numbers only):')

password = input()

if password.isalnum():

break

print('Passwords can only have letters and numbers.')

Enter your age: 32 Select a new password (letters and numbers only): 23er

display_quiz(path+"string4.json", max_width=800)

The replace() methods¶

The replace() function is like a "search and replace" operation in a word processor:

greet = 'Hello Bob'

nstr = greet.replace('Bob','Jane')

print(nstr)

Hello Jane

The join() and split() Methods¶

The join() method is useful when we have a list of strings that need to be joined together into a single string. The join() method is called on a string, gets passed a list of strings, and returns a string. The returned string is the concatenation of each string in the passed-in list.

print(', '.join(['cats', 'rats', 'bats'])) #Separated by comma

print(' '.join(['My', 'name', 'is', 'Simon'])) #Separated by white space

cats, rats, bats My name is Simon

' and '.join(['cats', 'rats', 'bats'])

'cats and rats and bats'

Notice that the string join() calls on is inserted between each string of the list argument. For example, when join(['cats', 'rats', 'bats']) is called on the ', ' string, the returned string is 'cats, rats, bats'.

The split() method does the opposite: It's called on a string and returns a list of strings.

'My name is Simon'.split()

['My', 'name', 'is', 'Simon']

By default, the string 'My name is Simon' is split wherever whitespace characters such as the space, tab, or newline characters are found. These whitespace characters are not included in the strings in the returned list.

You can pass a delimiter string to the split() method to specify a different string to split upon:

'cats, rats, bats'.split(',')

['cats', ' rats', ' bats']

A common use of split() is to split a multiline string along the newline characters:

spam = '''Dear Alice,

How have you been? I am fine.

There is a container in the fridge

that is labeled "Milk Experiment."

Please do not drink it.

Sincerely,

Bob'''

spam.split('\n')

['Dear Alice,', 'How have you been? I am fine.', 'There is a container in the fridge', 'that is labeled "Milk Experiment."', '', 'Please do not drink it.', 'Sincerely,', 'Bob']

Passing split() the argument '\n' lets us split the multiline string stored in spam along the newlines and return a list in which each item corresponds to one line of the string.

Removing Whitespace with the strip(), lstrip() and rstrip() Methods¶

Sometimes you may want to strip off whitespace characters (space, tab, and newline) from the left side, right side, or both sides of a string. The strip() string method will return a new string without any whitespace characters at the beginning or end. The lstrip() and rstrip() methods will remove whitespace characters from the left and right ends, respectively.

spam = ' Hello, World \n'

spam.strip()

'Hello, World'

spam.lstrip()

'Hello, World \n'

spam.rstrip()

' Hello, World'

Exercise 3: When editing the markdown document, you can create a bulleted list by putting each list item on its own line and placing a - in front. But say you have a really large list to which you want to add bullet points. You could just type those - at the beginning of each line, one by one. Or you could automate this task with a short Python program! For example, if I have following text:¶

Lists of resources

Lists of books

Lists of videos

Lists of blogs

After running the program, the text should contain the following:

- Lists of resources

- Lists of books

- Lists of videos

- Lists of blogs

text = """Lists of resources

Lists of books

Lists of videos

Lists of blogs"""

# 1. Separate lines into list using string method.

lines = text.______("\n")

# 2. Add -

for i, line in enumerate(lines): # loop through all indexes for "lines" list

lines[i] = _______ # add - to each string in "lines" list

# 3. Use string method to conctenate list of strings back to string

text = "\n"._______(lines)

print(text)

from jupytercards import display_flashcards

fpath= "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/phonchi/nsysu-math106A/refs/heads/main/extra/flashcards/"

display_flashcards(fpath + 'ch6.json')